Today, more than ever, we understand that doctors are under immense pressure. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many health systems have changed the way they work to minimize face-to-face appointments.

Traditional first points of contact between patients and the health system, such as general practitioners (GPs), urgent care centers, and emergency departments have to prioritize COVID-19 patients. However, there is also growing concern about patients experiencing serious non-COVID-19 symptoms during the pandemic. 1 This could lead to missing new diagnoses of other urgent conditions.

Traditionally, in many countries, a phone call to a GP’s receptionist was the main form of triage most of us would experience. This ensured that those with urgent needs would get an appointment first while others could be seen at a later time. With the increased demand, however, this system seems outdated. Patients have to call repeatedly, wait in a telephone queue, and make their case to someone without medical training.

Increasingly, digital alternatives such as online symptom checkers are being evaluated. 2 Online symptom checkers ask patients a series of questions about their medical history and new symptoms to help determine possible causes. Patients can submit their issues in their own time and at any time of day. There is no limit to the number of simultaneous users. The use of intelligent software, including AI, means that patients can both be directed to appropriate care and also receive helpful information to manage their symptoms.

But how can we evaluate how well such systems might work in practice? Ideally, they should be suitable for a wide range of users. This should include adults, pregnant women, and caregivers on behalf of family members. They should cover a comprehensive range of conditions, including physical issues, mental health conditions, and issues both benign and life-threatening.

The suggestions should be very similar to those that might be considered by a human GP. Advice levels should protect users without unnecessarily directing them to the emergency department.

These are the questions that Ada and a team of doctors and scientists set out to answer in a new study, published in December 2020 in the prestigious BMJ Open. The team consisted of experienced doctors, clinical researchers, data scientists, and health policy experts. They designed a study to compare 8 popular online symptom assessments both with each other and with a panel of 7 human GPs.

To ensure a fair comparison, the team used ‘clinical vignettes’. These included fictional patients, generated from a mix of real patient experiences gleaned from the UK’s NHS 111 telephone triage service and from the many years’ combined experience of the research team. In total, some 200 clinical vignettes reflected a typical GP caseload, such as “abdominal pain in an 8-year-old boy” or “painful shoulder in a 63-year-old woman”.

Using a procedure analogous to the examination of medical doctors in training, the participating GPs received the vignettes over the phone and were allowed to ask follow-up questions. Then they were asked to suggest the conditions they thought might be causing the symptoms. For the online symptom checkers, a different team of doctors entered the vignette details via smartphone, taking careful notes and screenshots as they went along.

The study set out to test 3 important factors.

- Coverage. Did the symptom checker allow the entry of a clinical vignette? Or did it reject it from being entered because, for example, the symptom checker was not configured to work with children?

- Accuracy. Did the symptom checker suggest a condition in its top 1, top 3, or even top 5 suggestions that matched the gold standard answer for each clinical vignette? How did its results compare to the GPs’?

- Safety. Where an online symptom checker was given a clinical vignette and subsequently offered some advice, such as staying at home to manage the symptoms, was this treated with the appropriate level of urgency? You wouldn’t want someone reporting the classic symptoms of a heart attack to stay at home and see if it gets better by itself

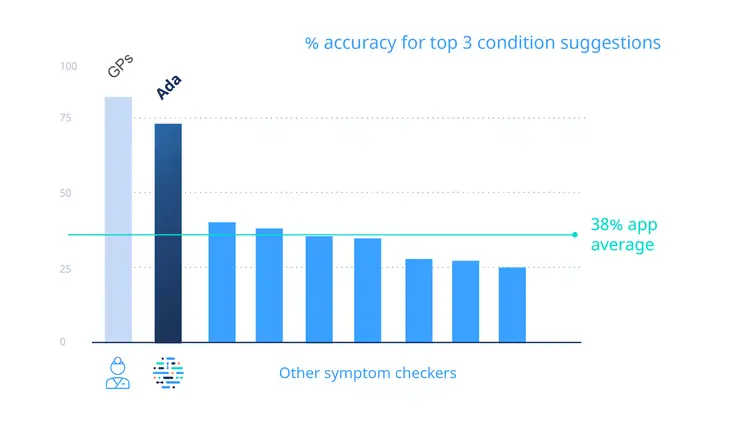

As you would expect, the results showed that human doctors have 100% coverage. They answered all vignettes with condition suggestions and advice, and 97% of the time their advice was considered safe. The human doctors were able to come up with the right diagnosis somewhere in their top 3 suggested conditions about 82% of the time. If that sounds low, remember that most medical conditions need further testing to confirm a diagnosis or a referral to a specialist.

How then did the online symptom checkers fare? We were pleased to see that Ada performed closest to the human doctors. Ada offered 99% condition coverage for the vignettes, gave safe advice 97% of the time (just like the human doctors), and 71% of the time came up with the right suggested conditions in the top 3.

The performance of the 7 other apps was far more variable. Some apps only covered about half of the vignettes, failing to suggest conditions for patients who were children, who had a mental health condition, or who were pregnant. Accuracy was highly variable too, from as low as about 23% to a high of just 43% – significantly lower than either Ada or the GPs.

Finally, safety. We saw that, while most other apps offered advice that seems in acceptable levels (80% to 95%), if they were deployed to thousands of users at once there could be many cases of potentially unsafe advice. A summary of the findings is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. % accuracy for top 3 condition suggestions

While this study shows how far technology has progressed in supporting medical triage, it also demonstrates that not all symptom checkers are created equal. Based on how they were developed, trained, and kept up to date, we must not assume that all tools have the same level of coverage, accuracy, or safety.

Because Ada was designed by doctors to emulate the diagnostic reasoning of a doctor we are proud to see how the tool has performed. But we know there is still much to be done. We also know that the best possible scenario is one in which Ada supports, not replaces, health workers.

Clinical vignettes are still not the same as assessing real patients. Future research needs to consider the overall impact on people’s health of the changes to the traditional health system workflow in these unprecedented times.

We hope that by continuing to improve our technology and sharing our analyses, we can support users while enabling vital health workers to focus on the enormous challenges they face every day.

Keep reading. Check the most recent peer-reviewed studies that evaluate Ada. Learn about health enterprise solutions powered by Ada.

- RCGP. “College urges parents not to shun childhood vaccinations during COVID-19 for fear of ‘burdening’ the NHS.” Accessed December 1, 2020.

- BMJ. “Evaluation of symptom checkers for self diagnosis and triage: audit study.” Accessed December 1, 2020.